The Heritage Path: wrecking-ball renovation and progressive museum-ification

Lijiang, China.

On Thursday, January 23, 2014, as the sun started to slide down and hide behind the mountains, we arrived in Lijiang.

Lijiang is an old water town, with hundreds of small canals and bridges, which is the reason why it is also known as Dayan, the big inker, in Chinese language. The town is located in Lijiang County, a rural district located in the north of Yunnan province, where it is surrounded by tall mountain chains. As a consequence of a massive investment in infrastructures, it is now possible to arrive by bus, but also by train and plane to Lijiang.

My friends and I had chosen the bus option. It had allowed us to admire the green hills covered with rice paddlies, that were shining on the sun of January, alongside the road linking Dali to Lijiang. We also enjoyed the experience of Chinese driving, on the dusty roads that were at the time under construction, turning the two-lanes-to-be into a four-lanes-as-long-as-it-fits track. It took us around four hours to arrive to Lijiang. We went off at the bus stop, in the new town of Lijiang, and took public transportation to reach the Old Town, Lijiang Gucheng. The bus stopped at a construction site across the road and everyone got off. We wondered a few minutes in the temporary paths, zigzagging between tine plate screens and wooden walkways.

Eventually, we arrived at an entrance of the Old Town, and it felt like arriving at the “Mulan Land” of some kind of theme park.

Two water wheels were slowly turning on a tiny river. A stele, headed by a typical roof made of grey tiles, reminded the visitors that the Old Town of Lijiang has been recognized as a World Heritage Site by the UNESCO since 1997. On its right, a red wall, covered with low-reliefs and maybe transcripts in Naxi language (the Naxi being the ethnic “minority” that represents the largest population in this region) hid the ancient city. The tourists, who were mostly Chinese, were taking selfies in front of the wheels, while so-called tour-guides, dressed in red jackets, sand sleeveless down jackets and black trousers, where showing pictures of typical Naxi-related attractions, desperately trying to find someone to register for their trip (or maybe scam).

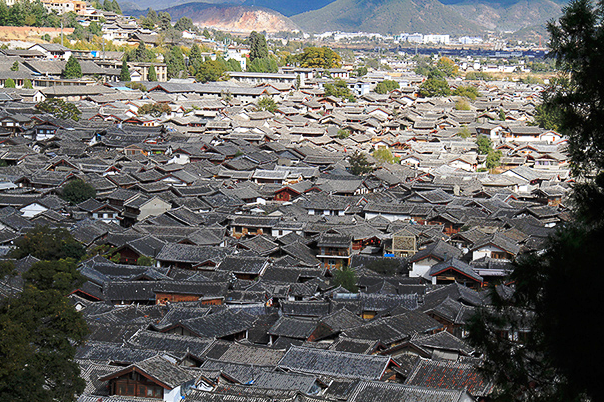

At dusk, all the sky’s colours had faded, and the last sun rays were bouncing on a sea of coal-like roofs. The small houses (they were only two-storey high) were forming lazy waves, imprisoned by the mountains, and forgotten by Time. Indeed, all the buildings in the Old Town are “in the style of” nineteenth century Lijiang, with structures and columns built in a burgundy wood, and roofs covered with grey tiles. In their book, Tami Blumenfield and Helaine Silverman emphasize on the fact that the buildings were built “in the style of” and are not the very-well preserved remains of the Old Dayan. In 1996, the Lijiang authorities took advantage of a fire that ravaged the city to tear down the remaining buildings that did not match the typical style of Lijiang’s architecture. Some lots were sold by the authorities to outsiders to rebuilt tourism infrastructures, in the traditional Naxi style.

Rooftops of the Old Town, picture by Beijing Hikers.

The “unsanitary” Sifang Jie (Square Streets)’s wet market, where locals used to shop daily for their vegetables and meat, was shuffled to a lane off the square in 1998, and definitely closed soon after, while the larger market outside the Old Town was also demolished in 2002. While the authorities did not plan to evict the residents (a fear expressed by the locals soon after Dayan was recognised a World Heritage Site), the natives progressively abandoned the Old Town. Living in this area had become inconvenient, whereas renting-out one’s house to outsiders who would run a guest-house or a shop was economically attractive. Thus, while the overall population of the Old Town reached 30,000 in 2008 (as compared to 25,379 in 1996), the number of individuals belonging to the Naxi minority sharply decreased, from 66.7% of the population, to around 30%, or even less.

Little by little investments, reconstruction and tourism had been turning Lijiang into a life-size museum, with its exhibits, reconstructions, restaurants, and souvenirs shops. On Sifang Jie, tourists can watch traditional dances performances and shop for tea and gifts.

Ironically, some of the economic actors involved in Lijiang’s cultural industry and economic life confessed to the geographer Su Xiaobo their absence of interest in the Naxi culture. In order to prevent the loss of Lijiang’s “authentic atmosphere”, the local authorities established a Business Permission Certificate system in 2003, and banned some bars, and karaokes. They also ruled that only locals could apply for a licence to run a tourism-based business, and that residential houses could not be sold to outsiders anymore but to the authorities. These initiatives have bred a growing resentment amongst the outsiders who run businesses in Lijiang. They feel excluded, and consider unfair to depend on their landlord for the obtention of a business licence. Moreover, most of the landlords ask not only for a rent, but also collect a fee for using the licence.

Besides, Lijiang’s booming tourism industry is evicting other types of economic activities and sources of revenue. In 2010, the tourism sector brought 14.4 billion yuan to the City, accounting for around 80% of its total revenues. Worried by this imbalanced situation, the authorities are now trying to revive other industries, and they are now betting on the expansion of “rural tourism”. At the fifth Yunnan-Taiwan Expo held in Lijiang in June 2016, the Vice Mayor of the city He Chunlei indicated that rural tourism is going to play “a crucial role in [Lijiang’s] development”. Interestingly, this concept appears to have recently attracted some attention in China, where experts and leaders emphasize on the importance of landscape farming (focusing on the scenery and the creation of a landscape pleasant to the eye of the tourist) and “folk custom touring” in remote villages. On the other hand, some documents published by the OEDC rather define this concept with reference to organic farming, farmhouse restaurants, and walking or riding tours. Other international associations also emphasize on the importance of a sustainable tourism and safe environment.

Riding on the rural tourism and development wave, the authorities of Yunnan province have indicated their willingness to “build 100 counties and 300 villages with ethnic characteristics while revamping 60 towns and 350 villages” over the next five years, the China Daily stated on June 23rd, 2016. Will the Old Town’s outskirts become an exotic resort planted in an artificial yet dreamy landscape (and under whose management?), will they turn into a “typical” countryside with sustainable cultures and practices, well-connected to the city, and will (organic) vegetables come back on Lijiang’s stalls? Time and local officials will tell.

*

Sources:

N. Backner, Tourism pressures on the old town of Lijiang, Yunnan, China, Ecoclub.com, August 22, 2015, access: ecoclub.com/headlines/reports/975-150822-lijiang-china

T. Blumenfield, H. Silverman, eds. Cultural Heritage Politics in China, Springer, 2013

China Daily,“Tourism Roundtable Held in Lijiang”, June 23, 2016

OECD, OECD Rural Policy Reviews: China 2009, p. 172

X. Su,“Moving to Peripheral China: Home, Play and the Politics of Built Heritage”, The China Journal, No. 70 (July 2013), pp. 148-162

H. Zhang,“The Sustainable Development of Tourism in Lijiang”, Millenium Assessments Reports, 2004